Lost in longitude or confused by contour lines? Want to know all the tips and tricks for getting the most out of your atlas? Curious if paper towns still exist? "Ask a Cartographer" is your opportunity to get the facts straight from the source. Tom Vitacco, Rand McNally Publishing’s Director of GIS is here to answer your burning questions, and geek out over fascinating map lore – one exploration at a time.

This week, we are discussing some more interesting company stories from the past…

Question: Rand McNally has been around for a long time. What are your favorite stories from Rand McNally’s history? (Part 4)

Tom’s answer: Ok, we are back with some more captivating stories from Rand McNally’s past, specifically related to the very early years in the late 1800s. I have already contributed three previous posts with some interesting stories if you missed them initially, and I hope you find these new anecdotes informative and educational.

Today, I will focus on an innovative production technique used by the cartographers when the company began, plus talk about some tales from around the time of the Great Chicago Fire that might be of interest as well.

Printing with Wax

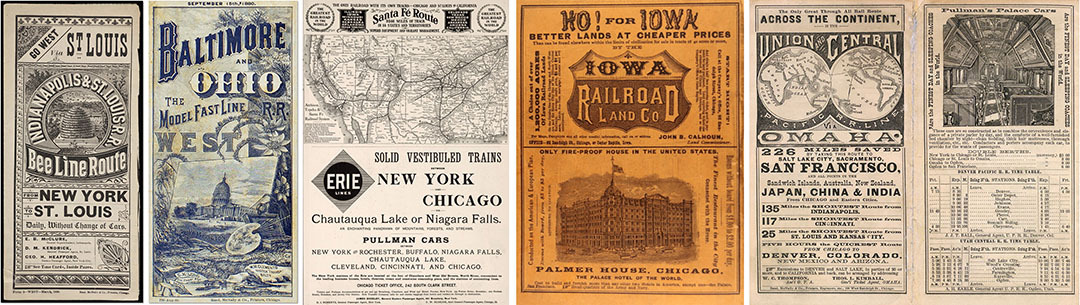

When the company first started, the initial business plans laid out by William Rand and Andrew McNally were focused on the booming railroad industry and printing their annual reports, timetables, guides, stationery, and tickets. The railroad industry accounted for much of their initial business, and soon the company was known as the premier railroad ticket printing house across the nation. Printing tickets was a large part of the company business for a long time – in fact when I first started in 1986 the company still had a ticket printing business – which was eventually sold off.

Pictured: Various railroad-related products from the late 1800s.

In 1871, the new partners introduced the Rand McNally Railway Guide, right after their business was destroyed in the notorious fire that devastated Chicago at that time, which is discussed in more detail below. In fact, the first Rand McNally maps appeared in the Railway Guide, eventually leading to larger maps of the United States and other regional maps along major rail routes.

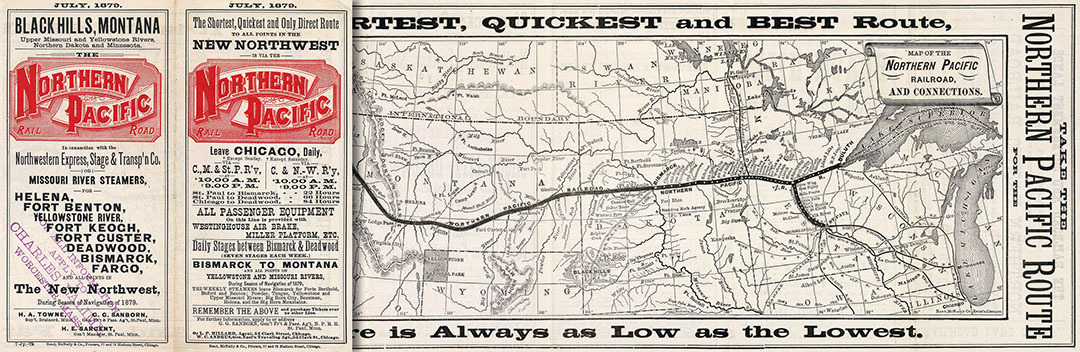

Pictured: The Rand McNally Railway Guide first introduced in the 1870s.

Rand McNally’s first large railroad map was published in 1876, called the New Railroad and County Map of the United States and Canada, and measured approximately 60 by 100 inches. We have a framed version of this map hanging on the wall in our building to this day…a wonderful reminder of our cartographic roots. Later that year, the company used the plates from this map to produce the famous Commercial Atlas and Marketing Guide, which was published for over a hundred years until the final edition in 2010.

The first railroad maps featured clean line work with detailed map content and were designed with the “traveling businessman” in mind. The maps provided information on the counties, towns, cities, rail systems, and road networks across the United States, but focused less on the hydrographic or physical features of the landscape. I find this fact interesting because we still feature this same type of map content in the road atlas today, since the atlases are designed for travel and planning.

Pictured: Largest railroad map produced at the time in 1876.

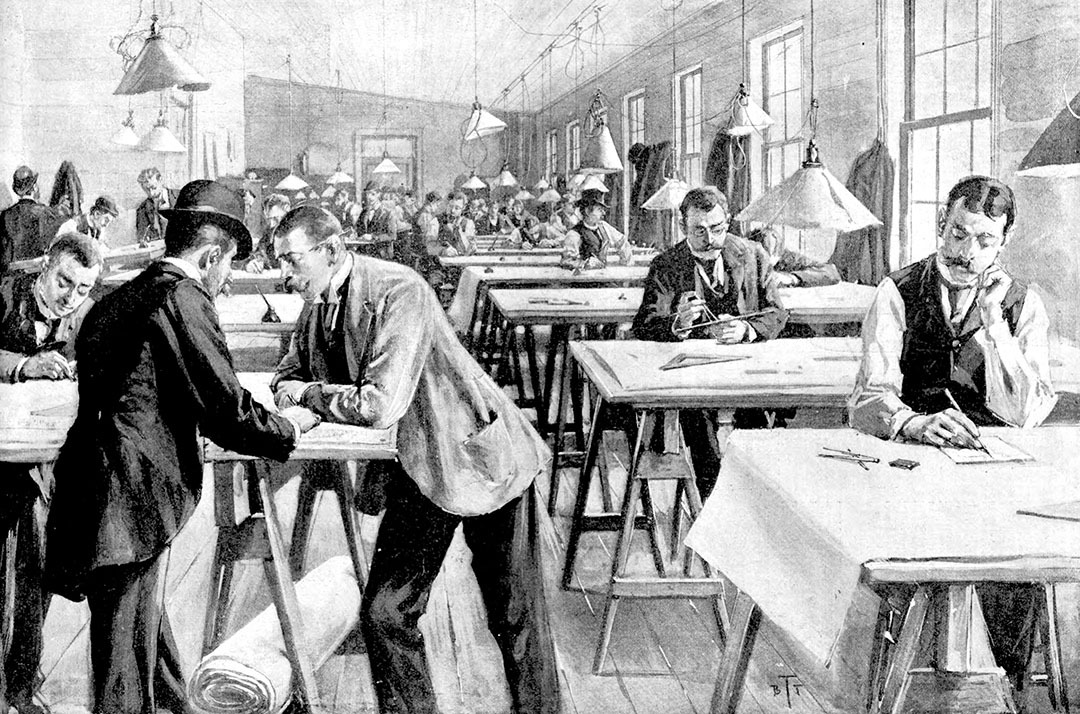

One of the intriguing Rand McNally stories I have heard is related to an innovative printing process called cerography, a wax engraving technique that Rand McNally & Company pioneered in 1872. This revolutionary technique allowed cartographers to combine half-tone illustrations, colored maps, and text all on the same page using one printing press.

Developed in the 1830s, cerography used an inexpensive metal plate covered with a layer of hardened beeswax, and the engravers would remove slivers of wax to construct the lines and symbols on the map. The plate was placed in a bath of copper sulfate which caused a thin copper coating to adhere to the waxed surface. The new copper plate could be used in a letterpress to produce a much larger quantity of prints than the traditional lithographic process, resulting in cheaper production costs and ultimately lower prices for the customer. The use of cerographic techniques is another example of how inventive the cartographers were back then.

Pictured: Northern Pacific Railroad map and guide from 1879.

The Great Chicago Fire

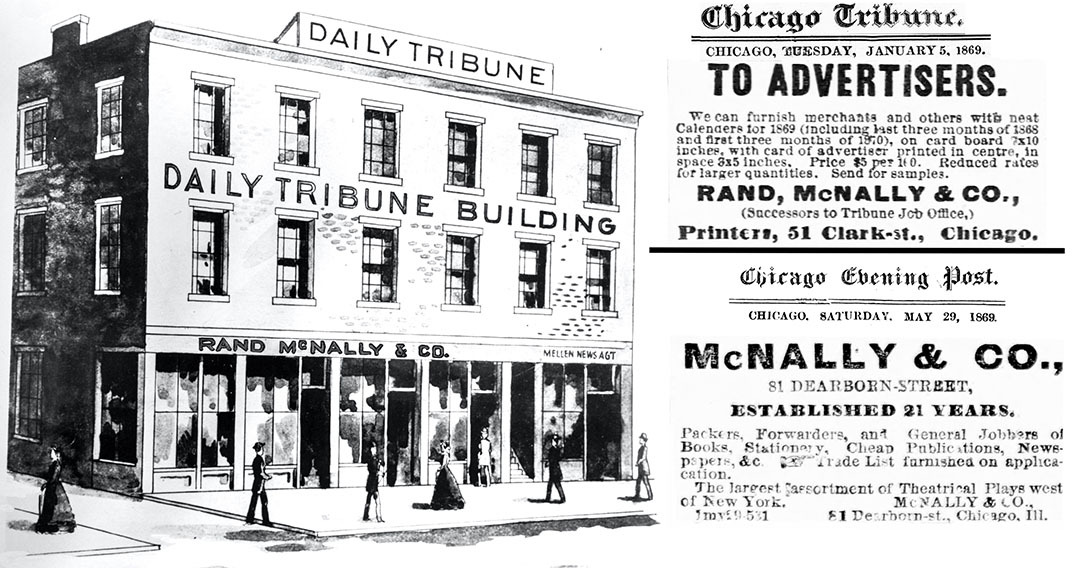

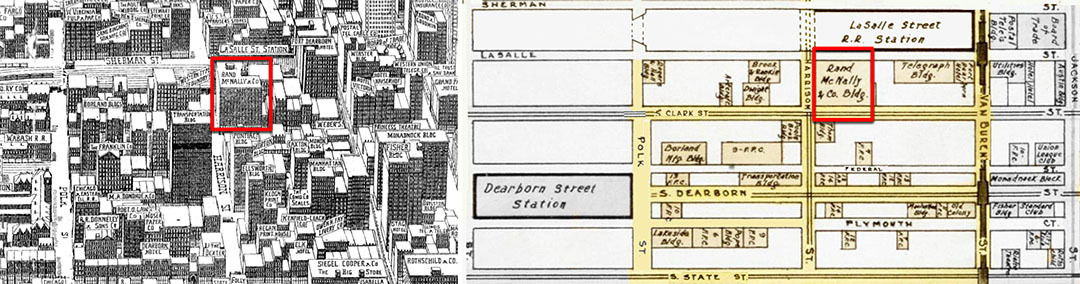

Another fascinating story from the early days of Rand McNally is one you may have heard before, but I wanted to provide a few other tidbits related to the old buildings in Chicago along Printers Row.

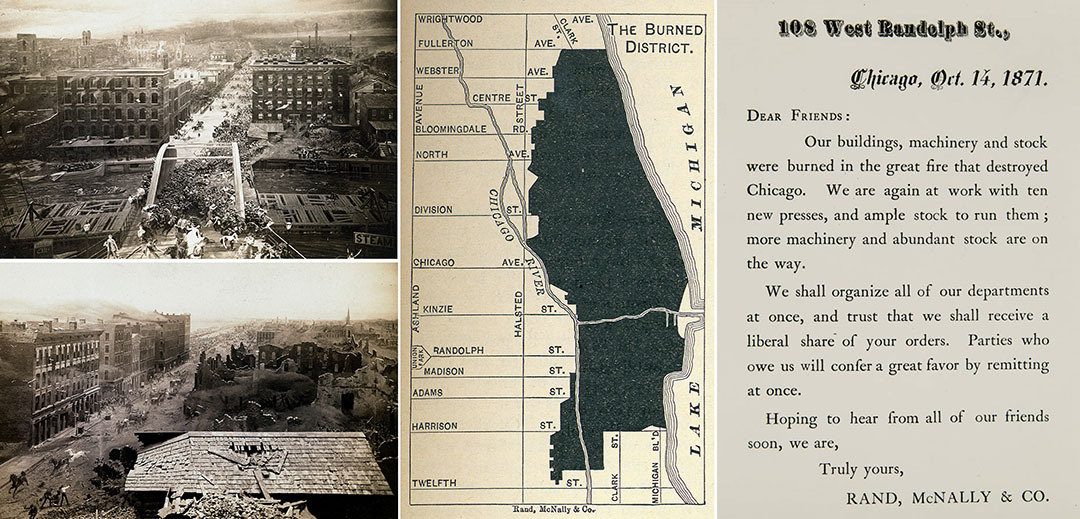

In October of 1871, a large fire destroyed much of Chicago, including over 17,000 structures and buildings. According to company lore, before the fire could reach their print shop, William Rand had workers move two new ticket printing machines, still in their packing crates, to Andrew McNally’s stables about three miles from the fire. When the flames threatened to engulf McNally’s home, he moved the machines to safety on the sands of Lake Michigan. The workers buried the printers in the sand to avoid the devastating heat and flames, but the shop on Clark Street and the McNally home were destroyed. Once the fire ended, the machines were retrieved, and the company was printing again three days later in a rented space on Randolph Street. Eventually, the company moved to Madison Street, and work resumed on the Railway Guides, maps and other products.

Pictured: Great Chicago Fire in 1871 along with a Rand McNally map showing the “burned district” at the time and a note the company sent out days later.

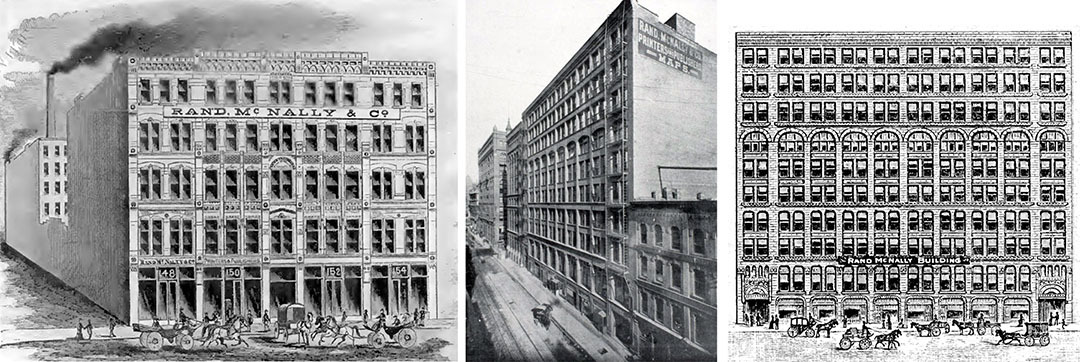

After the fire, most printers had moved their plants to a more central commercial district which became known as “Printers Row”, a major hub for printing and publishing in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Rand McNally had a location there for many years, including the facility at 536 South Clark Street. The area thrived due to its proximity to the newly opened Dearborn Station. The train depot became a transportation center for printers, with paper and other materials arriving while the printed books and maps were shipped out.

Around this time, new “steel-framed skyscrapers” were being built along the long, tight streets in Chicago, which were perfect for typesetters and book publishers in the days before automation. The buildings were constructed tall and very narrow to allow for good natural light, ideal for detailed typesetting, drafting, and press work. Before the advent of electric lights, engraving and cartography was performed under natural light with drafting tables positioned by the windows in each building.

Finally, Rand McNally was the first print house in Chicago to install new incandescent light bulbs throughout their plant. The lights offered a great advantage over gas lights which tended to distort colors. The more I learn about some of the company history, the more I realize just how truly forward thinking the company was back in those days!

Thanks again for the question! As I mentioned, we will occasionally continue with this topic in future blog posts since we have many more stories from Rand McNally’s history that hopefully are interesting and educational to our readers.

Feel free to submit your map or cartography questions below and check back soon for another installment of "Ask a Cartographer".

Have a question for our cartographer? Email us at printproducts@randmcnally.com with “Ask a Cartographer” in the subject line and your question could be featured next.